Learning through Empathy

/ I was lucky enough to spend last Friday morning at a café in San Francisco’s Ferry Building. Recently I’ve made a habit of spending Fridays there. I don’t live in San Francisco but I tend to have meetings in SF, which means the Ferry Building often becomes a bit of a home base for me. There’s plenty to eat and drink, and it’s light, bright, bustling with energy and just a bit chaotic – all good things in a vibrant city space!

As much as I love the frenzy and noise of the Ferry Building, it can also feel lonely here at times. Just like in any big city, being surrounded by strangers can lead to an awesome and liberating feeling of anonymity. On the other hand, sitting in a room watching everyone else laugh, eat and connect with their friends and family can leave a person feeling alone and cut off.

I was lucky enough to spend last Friday morning at a café in San Francisco’s Ferry Building. Recently I’ve made a habit of spending Fridays there. I don’t live in San Francisco but I tend to have meetings in SF, which means the Ferry Building often becomes a bit of a home base for me. There’s plenty to eat and drink, and it’s light, bright, bustling with energy and just a bit chaotic – all good things in a vibrant city space!

As much as I love the frenzy and noise of the Ferry Building, it can also feel lonely here at times. Just like in any big city, being surrounded by strangers can lead to an awesome and liberating feeling of anonymity. On the other hand, sitting in a room watching everyone else laugh, eat and connect with their friends and family can leave a person feeling alone and cut off.

A few weeks ago, I had an experience that left me feeling particularly isolated and alone, one that I thought I’d share in the hope that it offers some interesting learning and questions.

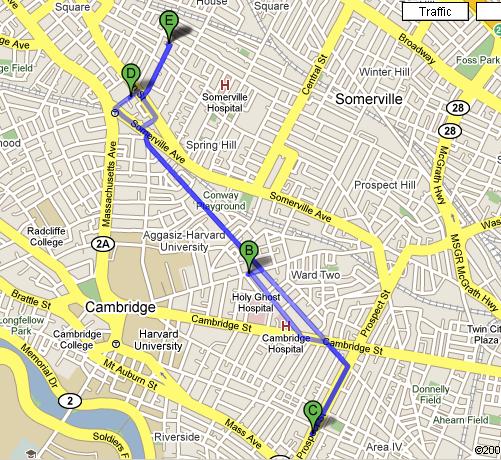

I was rushing like always to get out of the house and catch my train to San Francisco. I had a lunch meeting scheduled at (surprise, surprise) the Ferry Building, and I didn’t want to be late. To get there, I planned to walk to the train station (10 minutes), ride the train (40 minutes), take another train (10 minutes), and then walk a bit more. I sprinted to the station and hopped on just in time.

As I went to grab my monthly train pass, my heart sank: I had forgotten my wallet. Oh my god, I thought, I got on the train without a ticket! I don't tend to make mistakes like this often, so I immediately got a bit angry with myself.

Then, a few moments later the bigger reality hit: I don’t have any money. At first I didn’t think this was a huge deal – I crossed my fingers that I wouldn’t get booted from the train for not having a ticket, and amazingly luck was on my side and I managed to make it all the way to SF.

But here’s where it got complicated. To get to the Ferry Building in time for my meeting, I had planned to board a city train. But without money, I couldn’t buy a ticket and I knew I wouldn’t make it on a second time for free. So I started walking, and walking, and walking. Finally, a mile and a half later I made it to the Ferry Building – out of breath and 30 minutes late! I apologized profusely as I met my lunch date and we headed toward the entrance.

But of course, then I remembered: we were supposed to have lunch, and I had no money. My companion was very understanding and even offered to pay for my meal, but after all that walking and the stress and embarrassment of the morning, I wasn’t hungry so I passed on his offer. So we chatted while he ate, and about an hour later, we parted ways.

As we said goodbye, though, I had an instant moment of clarity and realized what was happening. It was late afternoon, and I was hot, exhausted and all of a sudden excruciatingly hungry. And I had no money. I was supposed to meet my husband a few hours later, and on the surface, waiting a bit before we met up didn’t seem unbearable.

But then I got to thinking – which was unfortunately becoming increasingly hard to do on an empty stomach:

Where do I go? Where can I wait?

Where’s the nearest bathroom?

Where’s the nearest water fountain?

All of a sudden, I felt alone and hopeless. I was hungry, thirsty, tired and completely by myself. As I wandered around and looked for a place to rest, I couldn't help but think to myself: this must be what it feels like to be homeless.

Now ok, in hindsight I will admit that was a sweeping generalization. In the grand scheme of things, I barely brushed the surface of understanding the challenges of being homeless. And rest assured that I did end up reuniting with my husband, over a delicious meal no less. Still, my afternoon without cash left a real imprint on me.

The truth is I’ve been thinking a lot about empathy these days. At IDEO, empathy is an integral component of what we call human-centered design. By putting ourselves in the shoes of others, we learn about people’s concerns, hopes, fears and perhaps most importantly, needs. And their needs are what we design for.

Take the current OpenIDEO challenge in partnership with Amnesty International as an example. Human rights, and unlawful detention specifically, is something that not everyone can relate to – so we’re using empathy to delve deeper into the experience a detainee or his/her family might go through. Empathy, in many ways, is the golden ticket that helps us design solutions successfully and with compassion and authenticity.

Last week David Brooks wrote an op-ed in the New York Times about the limits of empathy. His central argument is that while empathy can be a tool for understanding, it can also lead to misguided efforts. Empathy, for example, can make us feel more compassion for cuter, more approachable causes – like puppies, sick babies, or polar bears. And empathy, he argues, doesn’t actually translate to action. Just because you empathize with a homeless person on the street doesn’t mean you’ll actually act to improve his circumstance.

I agree with Mr. Brooks that empathy doesn’t guarantee action. Since reading his article, I’ll admit that my brush with empathy hasn’t exactly changed my behavior or inspired me to act differently.

I do however believe that empathy guarantees awareness.Without sounding overly dramatic, in the span of just a few hours that day, I was transformed. As I walked around, staying close to the restrooms and considering where I might find free snacks, I realized that I no longer felt like Ashley. Instead, I felt invisible, embarrassed, and to be honest even a little emotional.

Now, thanks to that experience a few weeks ago, I have at the ready some very tangible touch points for how it feels to be someone else. To be in a different place, in a different body and live under very different but very real constraints. Has my heightened empathy motivated me to reach into my pocket and give money to someone on the street? No, not yet. But have I approached my interactions, my work, and my personal life differently thanks to this renewed awareness? Absolutely. And I think that’s a great place to start.